Coping with Change

Most people with Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) have difficulty coping with change. This varies from person to person and can be a real problem for those families affected. Change can be anything from a substitute teacher at school, to a different route being taken in a car trip or a new cup being used. Change can also occur suddenly and unexpectedly, as in an electrical blackout. A bad reaction to change may result in the person with PWS refusing to comply with requests, routines or plans and can quickly escalate into perseveration (repeated questions or comments), arguments and aggression. “Shutdown” is another typical response to the anxiety associated with change. These responses can be stressful for families as they often occur at the most inconvenient times.

Why do people with PWS have difficulty coping with change?

The problem is thought to be linked with the inability to “switch” attention from one thing to another. People with PWS generally find it more difficult to switch attention. Researchers from the UK have shown that the greater difficulty a person with PWS has in switching their attention from one thing to another, the more resistance they show to change. It is also known that people with PWS tend to prefer repetitive routines and often exhibit ritualistic or inflexible behaviours. Although varied in their reactions to change, they all feel “safe” with set schedules and expectations. If a change can be predicted in advance, it is possible to use strategies to avoid much of the anxiety that may otherwise result from the change occurring.

What works to avoid anxiety related to change

These are simple and practical strategies that help to minimise the reaction to predicted change:

- Discuss a back-up plan in advance. For example, you could agree to buy pears if there are no apples at the fruit shop. The fact that this is discussed in advance can prepare the person for a different situation to the one they are expecting.

- Thoroughly plan all details and double-check things with the person with PWS and with others. Occasionally the person with PWS has an expectation that you are not aware of. For example, they may expect that you will be stopping for a cup of coffee on the way home, however if you are not aware of that and drive directly home, that would be perceived by them as a change. So it is always helpful to go over the details of any plans, beforehand.

- Agree on some rules for an outing. For example, a rule that “If there is any yelling for any reason we will return home.” Before the outing remind the person of the rule, using positive terms eg “your best behaviour will mean we can finish the trip and won’t need to come home early”. A set consequence of bad behaviour can be hard to enforce at the time, however, going home once can stop a lot of problems in the future.

- Praise the person whenever change is accepted graciously.

- Use picture-boards or written routines. Any change to routine is added to the board in advance. For example, a schedule could be written for the week. Doctor’s appointments or variations in the normal week can be written on it. If the person with PWS has any problems with the plans they can tell you in advance so, hopefully, any problems can be discussed and a solution can be negotiated.

What works to limit reaction to an unpredicted, last minute change of plans?

At times, unpredicted and unplanned change does occur. If you are fortunate enough to be able to respond quickly you may be able to reduce anxiety.

Below are some strategies that parents and carers have found successful in similar situations

- Give a solution before explaining the change. For example if a favourite coffee shop is closed for renovations, start by saying, “We are going to have coffee today at another coffee shop. That’ll be different, won’t it! We can ask them to make it just how you like. The coffee shop we like will be open again next week but it is closed today so we can’t go there today.” The last piece of information given in this example is the fact that the shop is closed and the fact that they will still get a nice coffee, comes first.

- Give a visual example of the problem or the change. For example if you were planning to move a cupboard into a room and it did not fit, showing a person with PWS the cupboard outside the door is better than trying to explain the problem in words. Simple sketches can at times be more easily understood than words.

- Be patient and calm as it may take some time for the change to be processed and then accepted.

- Try to point out the positive aspects that are involved in the change.

- Expressing shock at the change, yourself, and asking the person with PWS to help in the situation can diffuse their reaction to the change if they are given some responsibility within the event.

Managing change is an important part of managing the overall well-being of a person with PWS. Effective management of change can reduce anxiety and improve outcomes in other areas such as health and behaviour management.

Even ‘good changes’, such as a holiday, can be a sources of stress for the person with PWS and need to be managed as a change to routine. Perseveration, increased anxiety and worry about what will happen while they are away and so on, are often seen. Not telling the person with PWS about something ‘good’ coming up for them is an option, but not always a good solution.

Working out changes with the person with PWS, so that a better result might be achieved next time, can be useful. For example: “ Next time, if you think your cat has been in a fight and might have an abscess, do you think it would be better to go straight to the vet instead of trying to fix it yourself?” If the answer is ‘yes’, then you can incorporate it into their guidelines – write it up on their pin-board, and make sure they know the new plan!

After an argument, or a ‘blow-out’, and when the person with PWS has become quiet and even remorseful, ask them what you can do to help them next time something like this upsets them. You may be surprised at their answers and often they can lead to positive results. For example: “Please leave me alone for a while,” “Please listen to me,” “Please don’t treat me like a child,” These sorts of agreements can often prevent a future argument or blow-out.

It’s all about compromise

As the person with PWS grows older, their behaviours may mellow. There is an expectation from the person themselves, as well as parents, siblings and family friends that they will be treated more and more like an adult. As parents and caregivers, we know this is not always possible, but we can sometimes be a little more flexible and trusting in certain areas. It is difficult to let go, and there will be times that the trust between you will be broken, but if you compromise, safely, often you can reach an agreement. Lack of judgement and poor emotional control are not visible when they are calm and happy, always pre-discuss consequences.

Practising increased, safe responsibility can facilitate positive behavioural change

For example: Carrying a set amount of money for a specific, pre-planned event, can encourage self confidence and trust. However, success with this will take much preparation, explanation and negotiation. Having a “back- up” agreement to cover times when such a compromise does not work successfully is essential, such as: “If you spend the money instead of using it for what we’ve discussed it will be best for you not to take the money next time. I will then continue to organise the payment so you are not tempted to spend it on food.”

People with PWS vary in personality and cognitive ability. Some people can cope with more responsibility than others. If monetary responsibility is not necessary it is best avoided so as not to set the person up for failure.

A parent says: The main thing about compromise is that if you are going to take something away from a person, you must always give something back. For example: “Unfortunately I cannot let you keep a dog in this house because we really don’t have room. But, you can keep a bird in a cage/goldfish in a bowl, and we could always arrange for you to help walk some of the poor dogs at the SPCA who never get a chance to go out”.

Appealing to their own sense of judgment (“we don’t really have room”) and getting them to see that fact; giving something back (goldfish, or bird, for example) and appealing to their sense of importance, of doing something for others (walking someone else’s dog), seems to work.

Preparing people with PWS for change gives the them the opportunity to cognitively and emotionally process what is to happen and how the change will effect them. It may take time and effort to prepare people for change but the results are usually worthwhile. However, if the person with PWS is stressed for a reason unknown to you or they are aware of anxiety you may be experiencing, difficult behaviour can occur despite your use of all of the above suggested strategies. Don’t feel like they or you have failed. Keep applying positive proactive strategies. In time, improvements will be noticed.

This article was written by IPWSO’s Famcare Board.

International Community

IPWSO was established so that PWS associations, families, clinicians and caregivers around the world could exchange information and support and have a united global voice under one umbrella.

Information for Medical Professionals

The latest medical and scientific research and information, plus guides into common medical issues affecting people with PWS.

Paediatric Association of Nigeria - 57th Annual Scientific Conference

IPWSO was proud to support a dedicated PWS symposium at the 57th Annual Scientific Conference of the Paediatric Association of Nigeria (PAN) Conference held 21-23 January 2026 in Ogun State.

Famcare Board Member, Dr Elizabeth Oyenusi, presented on the clinical features, diagnosis, and management of PWS, while Dr Oluwakemi Ashubu shared the first genetically confirmed case of PWS in the country - an important milestone. The session attracted over 104 delegates and sparked a lively discussion.

IPWSO also hosted an exhbition table throughout the 3-day conference, distributing educational materials and engaging directly with healthcare professionals.

We are hugely grateful to Dr Oyenusi, Dr Ashubu and Dr Oladipo (Senior Registrar) for their support in making this educational oureach possible - helping to strengthen awareness and improve early diagnosis of PWS in Nigeria. Funding for this event was kindly provided by Friends of IPWSO (USA).

Global Newborn Society Inaugural Conference, Sweden

The Global Newborn Society’s 1st Conference took place in Uppsala and Stockholm, Sweden, from 2-4 November 2025, marking an exciting milestone for the organisation’s international community.

We were delighted that Dr Susanne Blichfeldt was invited to deliver a plenary lecture on behalf of IPWSO, titled “Neonatal Hypotonia: Clinical Features Seen in PWS That Can Help Differentiate It from Other Congenital Disorders with Similar Symptoms.”

The inaugural event brought together a diverse audience of physicians, nurses, and social care leaders from around the world. The programme was wide-ranging and stimulating, featuring cutting-edge discussions on newborn health, early diagnosis, and innovative care practices - setting a strong foundation for future collaboration within this growing global network.

ASPED 2025, Dubai, UAE

The 6th conference of the Arab Society for Paediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes was held in Dubai over two days on the 26th and 27th September 2025. IPWSO was invited to be a partner and to present at a session on PWS. The conference was attended by over 400 paediatric endocrinologists from more than 20 countries in the Middle East and North Africa. Charlotte Hoybye and Tony Holland attended and presented on behalf of IPWSO and Dr Sarah Ehtisham described her experience seeing patients with PWS in the United Arab Emirates. IPWSO hosted a stand for the whole conference.

In conversation many attendees reported seeing people with PWS and described the challenges they faced, particularly with the management of behaviour problems. Some felt nervous about starting growth hormone as they had had no experience prescribing it to infants with PWS.

Approximately 100 attendees joined the IPWSO mailing list and attendees were very keen to gain knowledge about PWS. Numerous memory sticks with information on PWS and printed material in English and Arabic were taken. Some attendees talked about establishing national or regional PWS Associations.

This was an extremely positive experience and hopefully attending this meeting has laid the groundwork for IPWSO to engage more fully in the Region in the future. We were very well looked after, and the organisers were excellent hosts.

EPNS 2025, Munich, Germany

Together with parents and representatives from the Prader-Willi-Syndrom Vereinigung Deutschland, we were proud to host a PWS exhibition stand at the 16th Congress of the European Paediatric Neurology Society, held in Munich from 8-14 July 2025. The event welcomed over 2,000 medical professionals from around the world.

We had the pleasure of engaging with attendees from Türkiye, Iraq, Palestine, Croatia, Moldova, the Philippines, Ukraine, North Macedonia, Kazakhstan, Armenia, and many local specialists.

Dr. Stefani Didt, Gesellschafter at Katholische Jugendfürsorge der Diözese Augsburg, kindly supported us at the stand and provided expert responses to clinical enquiries. We hope these international connections will contribute to raising awareness about IPWSO’s work, particularly in improving access to genetic testing in underserved regions.

We also highlighted the new treatment for hyperphagia and shared our recent publication, "Improving Mental Health and Well-being for People with PWS."

Sincere thanks to our colleagues from PWS Vereinigung Deutschland and to Dr. Didt for their invaluable support.

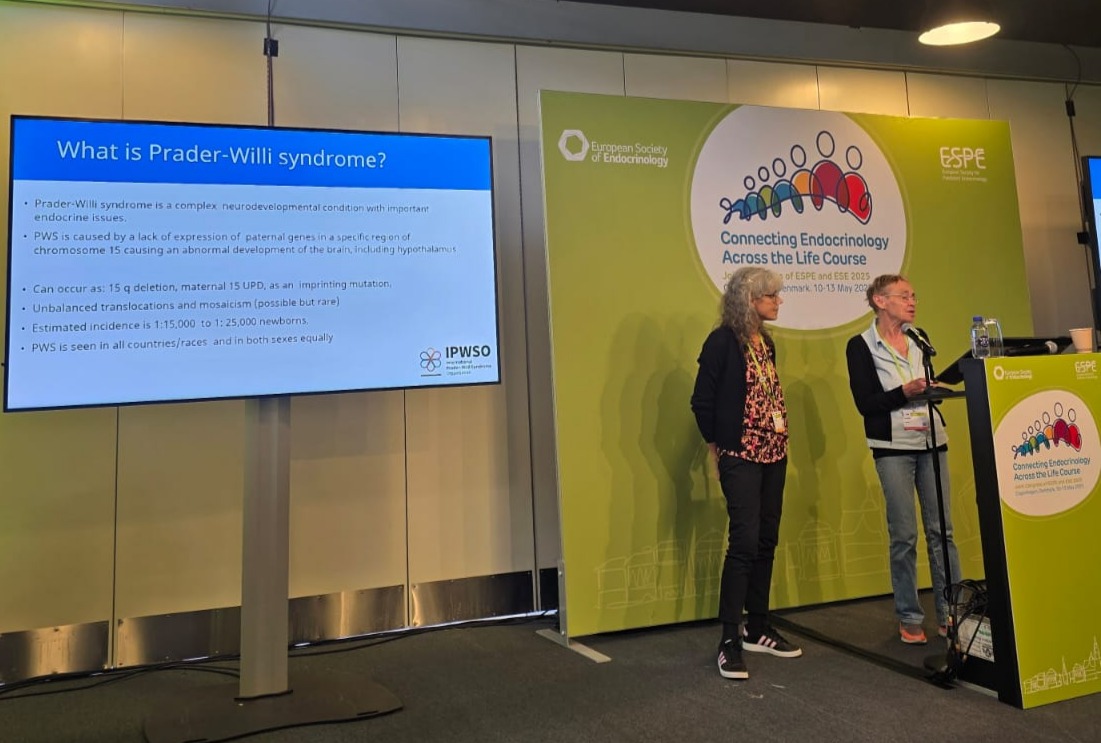

ESPE-ESE 2025, Copenhagen, Denmark

IPWSO was honoured to participate in the recent Joint Congress of the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology (ESPE) and the European Society of Endocrinology (ESE), held in Copenhagen from 10–13 May 2025. This important event provided an invaluable opportunity to raise awareness of Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) among a broad international medical audience.

IPWSO was represented by our CEO, Margaret Walker, along with Dr Charlotte Höybye from Sweden and Dr. Susanne Blichfeldt from Denmark—both esteemed members of IPWSO’s Clinical and Scientific Advisory Board.

Dr Blichfeldt noted that this congress is a major event in the clinical academic calendar and has a particular significance as it marks the first-ever joint meeting of these two prominent societies. Despite its European designation, the congress attracted participants from around the globe, including delegates from the Middle East, Africa, the United States, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand.

IPWSO’s educational booth was strategically positioned within the Patient Advisory Group area dedicated to rare disease organisations. As part of the programme, we were invited to deliver a 30-minute presentation during the Patient Voices Session. Dr Charlotte Höybye and Dr Susanne Blichfeldt presented on Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS), with a focus on genetics, endocrinology, and clinical manifestations. Our presentation, along with many others, was recorded and is now available on demand via the ESPE-ESE congress platform.

PWS was prominently featured throughout the congress. In a session on the transition of care for patients with rare diseases, Dr. Maithé Tauber (Toulouse, France) discussed the specific challenges associated with the transition period in PWS. She emphasized the need for multidisciplinary care and ongoing specialist follow-up in adulthood through dedicated PWS clinics.

Another session addressed medical and clinical management in both children and adults with PWS, again highlighting the critical importance of a smooth transition from paediatric to adult care and the role of specialised clinics. The session included an in-depth discussion on hyperphagia in PWS, exploring its profound impact on individuals and their families. Management strategies were reviewed, and a new medication, Vykat, was presented as a potential treatment for hyperphagia.

In addition, there was a strong presence of scientific posters on PWS from various countries, covering a wide range of topics such as hormonal therapies, genetic findings, ageing, and guidance for families. A total of 33 posters focused on PWS, reflecting a growing global interest and commitment to advancing knowledge and care in this area.

We were greatly encouraged by the high level of engagement and the visibility given to PWS throughout the congress. This increased awareness brings hope that more children will be diagnosed earlier and receive appropriate, specialised medical care from childhood through to adulthood.

ASPAE 2025, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire

After Yaounde (Cameroon 2023) and Alger (Algeria 2024), IPWSO was pleased to be present at the 16th Annual Congress of the African Society of Paediatric and Adolescent Endocrinology (ASPAE), at the invitation of Dr Kouamé Hervé Miconda, Programme Co-organiser. Prior to the main conference, IPWSO, in partnership with Dr Micondo, organised a dedicated PWS workshop which attracted 60 professionals - paediatricians, endocrinologists, doctors, students, nurses, and midwives.

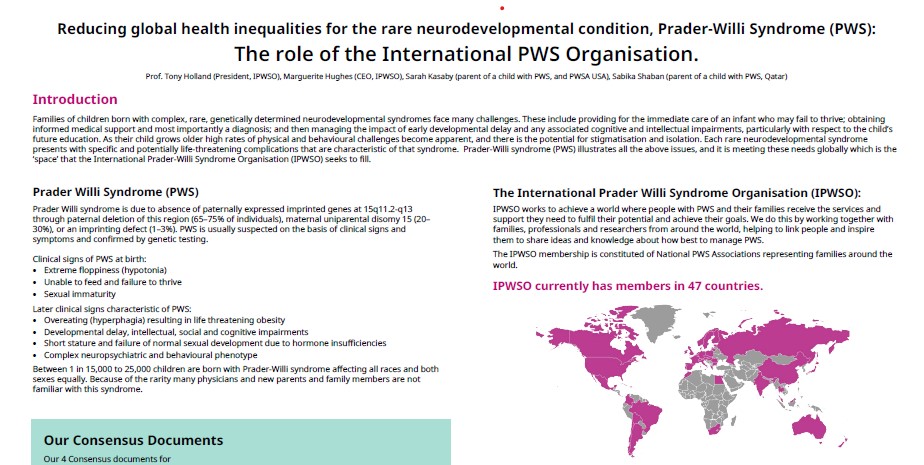

MENA 2025 Abu Dhabi, UAE

The Middle East and North African (MENA) conference for Rare Diseases was held in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, between 17th and 20th April 2025. Tony Holland represented IPWSO at this meeting and presented a poster about our work. The conference was attended by clinicians, genetic councillors, scientists, and other health disciplines from across North Africa and the Middle East. The conference was in English as many clinicians in this part of the world are from elsewhere and not Arabic speakers. The conference was of a very high standard and ranged broadly across many rare genetically determined conditions as well as there also being discussions about how to develop services and how to seek approval for new treatments. Our poster was one of five that was selected as the best posters exhibited at the meeting. Tony said, "My experience of the conference was very positive and I am sure there are opportunities that can be built on. Being part of the endocrinology meeting, which is likely to be attended by endocrinologists from across the whole region, provides a wonderful opportunity to engage more fully with clinicians most likely to see people with PWS".

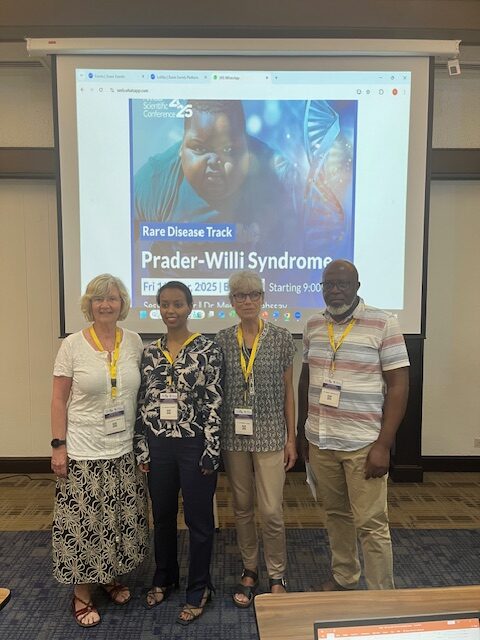

Kenya Paediatric Association Annual Scientific Conference, Monbassa, Kenya

Dr Menbere Kahssay and Dr Renson Mukhwana, Aga Khan University Hospital, Nairobi represented the Kenyan team and, together with Drs Constanze Laemmer and Dr Charlotte Höybye, managed the IPWSO educational booth at our first meeting in this region.

A dedicated session on PWS significantly raised awareness and knowledge about the syndrome among paediatricians and allied health professionals.

Dr Kahssay said, "We were able to have track and plenary session and four days interaction with the participants at the booth.

The PWS session focused on case experiences and regional differences in PWS management. Thanks to IPWSO’s support, Drs Charlotte Hoybye and Constanze Lammer joined as expert speakers, sharing their valuable experiences in managing PWS across the neonatal, childhood, and adult stages".

Dr Menbere Kahssay and Dr Renson Mukhwana presented genetically confirmed local cases, highlighting diagnostic challenges and treatment approaches.

Third Biennial Rare Diseases Conference, Rare X, Johannesburg, South Africa

Karin Clarke and Molelekeng Sethuntsa organised the IPWSO exhibition table at this event in Johannesburg from 14-17 February 2024. Molelekeng attended the conference and reported on the excellent discussions that focused on the challenges of early diagnosis, especially in Africa, centres of excellence, and ways that the Department of Health, WHO and RDI can improve detection and treatment of rare diseases.

6th RARE Summit 2023, Cambridge, UK

Tony Holland, President, and Agnes Hoctor, Communications and Membership Manager, represented IPWSO at the 6th RARE Summit organised by Cambridge Rare Disease Network on 12 October, 2023.

MetaECHO® 2023, Global Conference, Albuquerque, New Mexico

The 5th MetaECHO® Global Conference took place from September 18-21 in Albuquerque, New Mexico. It celebrated 20 years of ECHO programmes and brought together ECHO leaders, partner teams, government officials, funders, policy makers, and industry experts to share retrospective work and thoughts on the future of ECHO. Our President, Tony Holland, presented a paper on “A Global ECHO Programme for the Rare Disorder – PWS", based on IPWSO’s Project ECHO programme.

EPNS 2023, Prague, Czech Republic

The 15th European Paediatric Neurology Society Congress (EPNS) took place from 20-24 June. Tünde Liplin, PWS Hungary, and Hana Verichová, PWS Czechia, represented IPWSO. Twenty-two people from countries including Georgia, Israel, Lithuania, Turkey, Italy, Slovakia, Romania, Netherlands, Bosnia Herzegovina, Belgium, Argentina, Norway, Serbia, India, and Australia subscribed to the "Stay in touch with IPWSO!" contact list. Tünde reported that many people came to the stand just to inquire and chat, the majority of whom were hearing about IPWSO and our work for the first time.

ECE 2023, Istanbul, Turkey

The European Congress of Endocrinology (ECE) took place from 13-16 May. We hosted an information table and were represented by IPWSO advisers, Constanze Lämmer and Charlotte Höybye, and also our Communications and Membership Manager, Agnes Hoctor. We were pleased to be given the opportunity to present on IPWSO and PWS at the Hub Session. The most exciting and important element for us was that the Turkish location meant that delegates came from many countries in Middle East as well as Europe.

ASPAE 2023, Yaoundé, Cameroon

We hosted an educational booth and presented at the round table on Obesity at this important Endocrinology conference hosted by the African Society of Paediatric and Adolescent Endocrinology (ASPAE) from 9-10 February. Read our blog about our visit.

ECE 2021, Online

We hosted an educational booth and gave a presentation at the European Congress of Endocrinology in May 2021.

ESPE 2019, Vienna, Austria

We exhibited at the European Society of Paediatric Endocrinology (ESPE) Conference in Vienna, Austria, which took place in September 2019. Find out more in our blog.

ECE 2019, Lyon, France

We exhibited at the European Congress of Endocrinology in May 2019.

Dr Ashubu discussing IPWSO's educational materials with delegates at our booth.

IPWSO was honoured to be invited to present at the Global Newborn Society's Inaugural Conference.

Dr Sarah Ehtisham presenting at ASPED 2025 followed by a panel discussion.

Colleagues from PWS Vereinigung Deutschland help manage our PWS stand at EPNS 2025. Many thanks to all the parents and carers for their invaluable support!

Dr Charlotte Höybye (Sweden) and Dr. Susanne Blichfeldt (Denmark) presenting at the ESPE-ESE Patient Voices Session - May 2025

Dr Blichfeldt and Margaret Walker (CEO) managing our IPWSO educational booth.

François Besnier, IPWSO's Vice President, meeting some of our travel fellowship delegates at ASPAE 2025.

IPWSO's poster achieves top award!

Many thanks to Drs Constanze Laemmer, Menbere Kahssay, Charlotte Höybye and Renson Mukwana for all their support at KPA 2025.